Trump threats loom over the long, complex and untested CUSMA review process

ISTOCK PHOTO

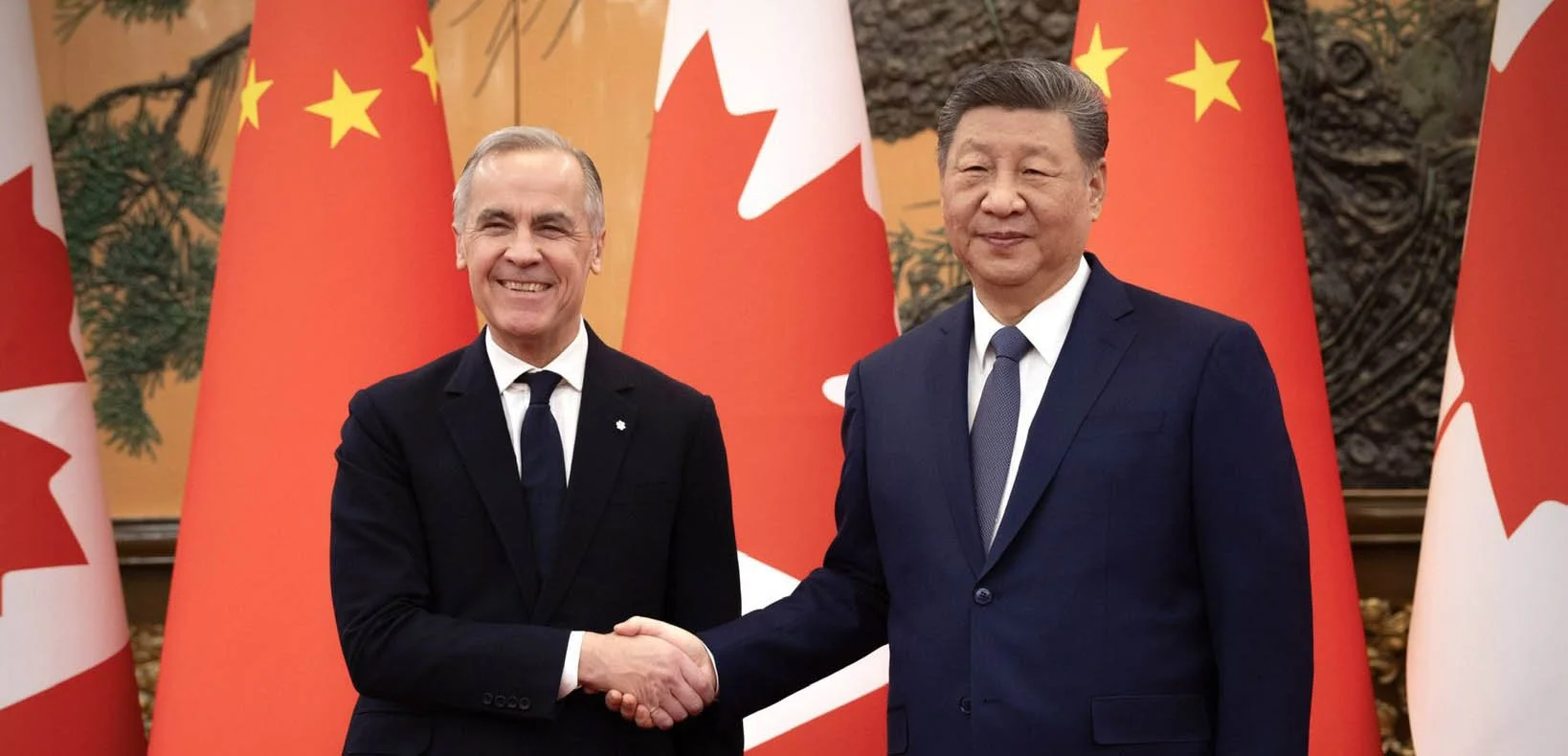

While U.S. President Donald Trump was musing this week about killing off Canada-U.S.-Mexico free trade, American business leaders were queuing up several blocks away in the U.S. capital to publicly beseech him to preserve the trade deal.

The scene at the hearings on the three-country trade pact (known as CUSMA here but USMCA by Americans) was a truly remarkable and unexpected vote of support for the 31-year-old trade integration arrangement that Trump has been slagging on and off for most of the past decade.

U.S. executives and trade groups, which have been generally afraid to express their dislike of the president’s destructive tariff campaign, used the consultations on the future of CUSMA to overwhelmingly call for the pact’s extension.

They were speaking at a three-day hearing held by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR)–consultations that are required as part of the U.S. government’s preparations for a review of continental free-trade that will formally begin on July 1, 2026.

CUSMA, which Trump helped negotiate and came into force in 2020, includes a complex, novel and untested “sunset” process.

The agreement is set to expire automatically after 16 years (in 2036) unless the three countries agree to extend it. To keep it from expiring, a formal joint review must take place in the sixth year after its creation, which is 2026. The review is conducted by trade ministers from the three countries under the rubric of the Free Trade Commission starting next July.

When it’s done, Canada, the U.S. and Mexico must each issue a statement saying whether it wishes to extend CUSMA for another 16 years, until 2042. If all three countries agree on an extension, the free-trade deal remains in force, with the next review due in six years, or 2032.

If any of the three nations does not formally express support for an extension, CUSMA will still continue to exist. But joint reviews of the agreement will be required to take place every year until the pact’s originally scheduled expiry in 2036.

Preparations in the form of consultations have been underway in the U.S., Canada and Mexico through the fall. This is leading up to the finalization of each countries’ objectives and strategies for the CUSMA review process.

The expectations and anxieties among people in all three nations are expected to build dramatically through the first half of 2026 as each country’s position becomes clearer. Crucially, for instance, the USTR must submit a report to the U.S. Congress in January laying out its assessment of USMCA, suggesting improvements and stating whether the trade agreement should be extended.

All three countries will provide recommendations to the Free Trade Commission for updates or reforms of CUSMA, and there are widespread expectations that the U.S. will use this process to try to negotiate changes to forcefully advance Trump’s U.S.-first trade objectives.

No one knows, of course, whether Trump will pay much attention to the views of U.S. business brought forth in the review process in his country.

And there’s also an escape clause in the whole trade arrangement. Outside of the review process, CUSMA allows any of the three partners to withdraw from the deal at any time by providing six months’ written notice.

Although Trump called NAFTA 2.0 the greatest deal ever after he helped negotiate it, he continues to talk about scrapping the agreement altogether.

“It expires in about a year, and we’ll either let it expire, or we’ll maybe work out another deal with Mexico and Canada,” Trump told reporters in the White House on Wednesday.

Observers said his use of the term “expire” showed he didn’t know how the whole review process works. But maybe what Trump said was more indicative than it might have seemed. If the White House were to give six months’ notice of withdrawal at the time of the Free Trade Commission’s review in July, the U.S. would be backing out of the three-country deal just about a year from now.